Immigration Law and Interment Camps in Texas - a digital exhibit > The Law of Crystal City

The Law of Crystal City

The Alien Enemies Act of 1798

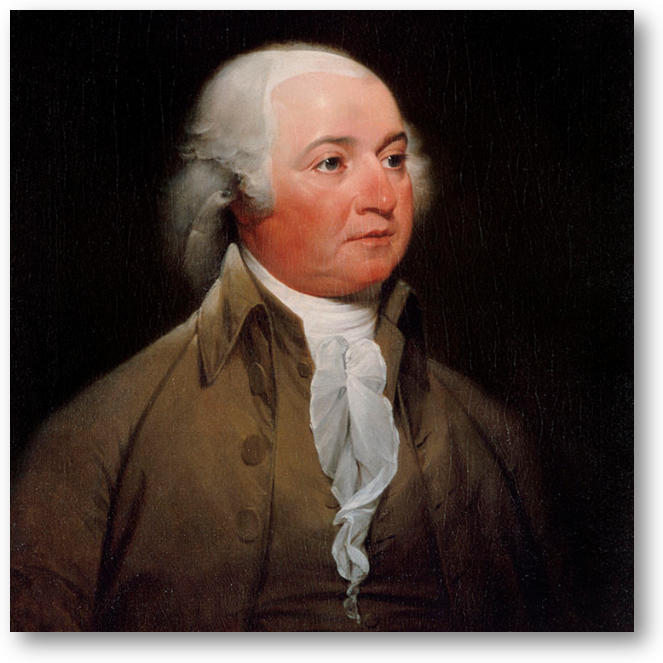

The Alien Enemies Act of 1798 was signed into law by President John Adams during the nation's 5th Congressional Session. Fear of war with France drove the legislation, much as fear of the Axis nations shaped the legal landscape during World War II. Designed to protect the nation against immigrants deemed hostile or dangerous, the Alien Enemies Act allowed the President to imprison and deport foreign residents. In effect, it created barriers to naturalization for non-citizens and allowed the President to retroactively revoke citizenship for natives of hostile nations. Nearly 150 years later, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued three presidential proclamations that were heavily influenced by the Alien Enemies Act.

Presidential Proclamations 2525, 2526, and 2527

Pursuant to The Alien Enemies Act of 1798, President Roosevelt issued three proclamations: 2525, 2526, and 2527. Issuing these statements was an expedient way to take action against Japanese, German, and Italian civilians who, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, were seen as potentially dangerous to the safety and security of the nation. These proclamations defined immigrants from hostile nations -- namely Japan, Germany, and Italy -- as alien enemies, and prescribed regulations for their conduct and control. Branded as a threat to the public interest, these enemy aliens -- even naturalized citizens -- could be detained or deported. On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the Secretary of War to establish and maintain military control zones as a necessary step in carrying out the internment of the targeted immigrant groups.

Joint Resolution Declaring War with Germany

On December 11, 1941, the United States Congress passed a Joint Resolution, pictured here, formally declaring a state of war with Germany. The declaration came four days after the attack on Pearl Harbor and three days after President Roosevelt proclaimed those of Japanese, German, and Italian heritage to be enemy aliens. In the famous speech that Roosevelt delivered just one day after the attacks on Pearl Harbor, he declared December 7, 1941 as "a date that will live in infamy." He also made public the nation's intent to enter the war with assurances that "this form of treachery shall never endanger us again." In just thirty-three minutes, with the stroke of a pen, the House and Senate unanimously declared war. Nationalist pride swelled throughout the country, and suspicion of foreigners, particularly those of Japanese and German descent, reached a new high. Thanks to Executive Order 9066, actions to evacuate and imprison Japanese civilians were taken without delay. Germans and Italians were targeted soon after, resulting in mass incarceration and rampant xenophobia.

Korematsu v. United States

According to Civilian Exclusion Order No. 34, all people of Japanese heritage were ordered to leave their homes and report to designated assembly centers where government officials would process them for relocation to internment centers all along the west coast. Fred Korematsu, an American-born citizen of Japanese heritage, defied the order by refusing to abandon his home in San Leandro, Calilfornia. As a result, he was arrested and convicted of evading internment, a conviction that he appealed all the way to the Supreme Court. Mr. Korematsu felt strongly that being expelled from his home and relocated to an internment facility was unconstitutional and a violation of his Fifth Amendment rights. The Supreme Court disagreed. A 6-3 majority on the court upheld his conviction and cited the nation's security as a greater concern than the Constitution's promise of equal rights.

Presidential Proclamation 2655

In the interest of national defense and public safety, Harry S. Truman issued Presidential Proclamation 2655 on July 14, 1945. This statement prescribed regulations "necessary and supplemental" to those previously established by President Roosevelt's proclamations, which declared Japanese, German, and Italian immigrants to be alien enemies. Proclamation 2655 extended this definition to include "all alien enemies now or hereinafter interned within the continental limits of the United States" and deemed them "dangerous to the public peace and safety" of the nation. As such, those interned in the camps, whose assumed loyalty to enemy governments was considered threatening and traitorous, could be removed from the United States by order of the Attorney General and required to depart from American soil. Removal letters like the one pictured here were issued to those who were ordered to depart.